Timber Needs Its Biobased Bedfellows: Why the Fastest Path to Decarbonising Construction is a Family Affair

The legitimate concerns remain

Not every timber operation in Australia, past or present, has been responsibly managed. Native-forest logging in particular has faced sustained and entirely justified criticism for its impacts on biodiversity, endangered species and habitat fragmentation. Those concerns are real, evidence-based and must stay firmly on the table.

The risk of throwing the baby out with the bathwater

Tony Arnel is right to warn that when those valid criticisms, rightly aimed at past practices, start to be applied to responsibly sourced plantation timber too, we risk losing one of our best tools.

Australia has a housing crisis and binding 2030 emissions-reduction targets. Responsibly grown plantation timber is one of the lowest-carbon structural materials we have at scale right now. If well-intentioned opposition unintentionally limits us from using more of it, we only make the already difficult tasks of decarbonising construction and delivering affordable homes even harder.

A constructive way forward

The answer is not to dismiss the criticisms, nor fall into a defensive “timber-is-the-only-answer” rhetoric. The answer is to keep the legitimate concerns where they belong, keep using responsibly grown plantation timber, and actively bring in its fast-growing biobased relatives.

Arnel describes timber as “the only mainstream structural material that’s indefinitely renewable” in his recent Fifth Estate article. [1] The intent is understandable, but the word “only” is both factually and strategically unnecessary. Engineered bamboo, made by laminating treated bamboo strips into strong, uniform beams and panels, much like glulam timber, is already code-approved in multiple jurisdictions for beams, columns and large-stud framing, with strength equal to the premium hardwoods Australian builders have long relied on. Hempcrete (hemp-lime composites) provides excellent infill insulation and non-structural blocks; engineered straw panels and mycelium composites are load-bearing or semi-structural in completed buildings today. Cross-laminated bamboo-timber hybrids have reached seven storeys. These are proven, ready-to-use materials that grow far faster than plantation trees.

The market sees the opportunity

The global bio-based construction materials market is projected to grow from ≈US$35 billion in 2025 to ≈US$195 billion by 2035, at a 19% compound annual growth rate.[2] The fastest-growing segments globally are precisely these non-timber biobased materials, bamboo, hempcrete, straw, mycelium and agricultural-residue panels, expanding at 15–20% annually or more.[3] In Europe, non-timber biobased insulation and infill already outpace timber volume growth in new Passivhaus projects. The pie is expanding rapidly, giving Australian industry a genuine chance to lead rather than follow.

Hybrids are already outperforming single-material designs

Real buildings prove the point today:

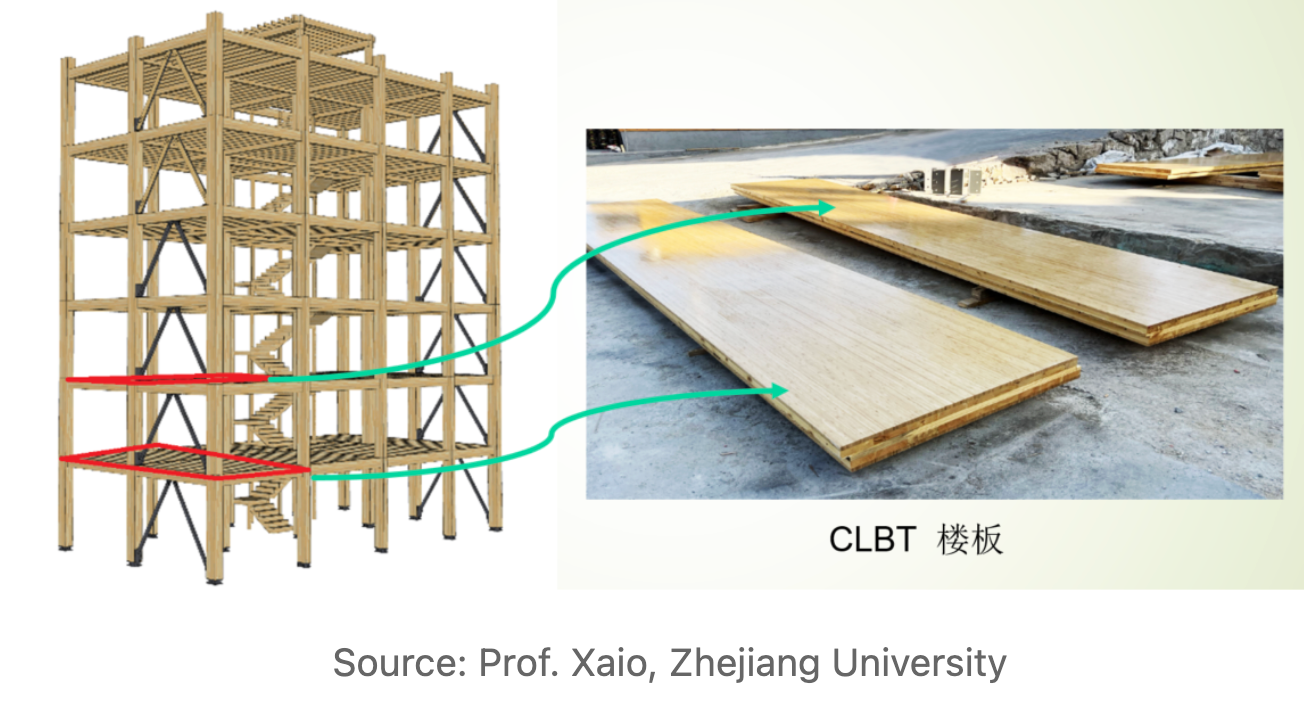

- Ninghai Bamboo Tower, China (Prof. Yan Xiao, Zhejiang University, 2024), seven storeys, cross-laminated bamboo-timber structure. Whole-life carbon 65–70% lower than concrete equivalent; 40% faster construction.[4]

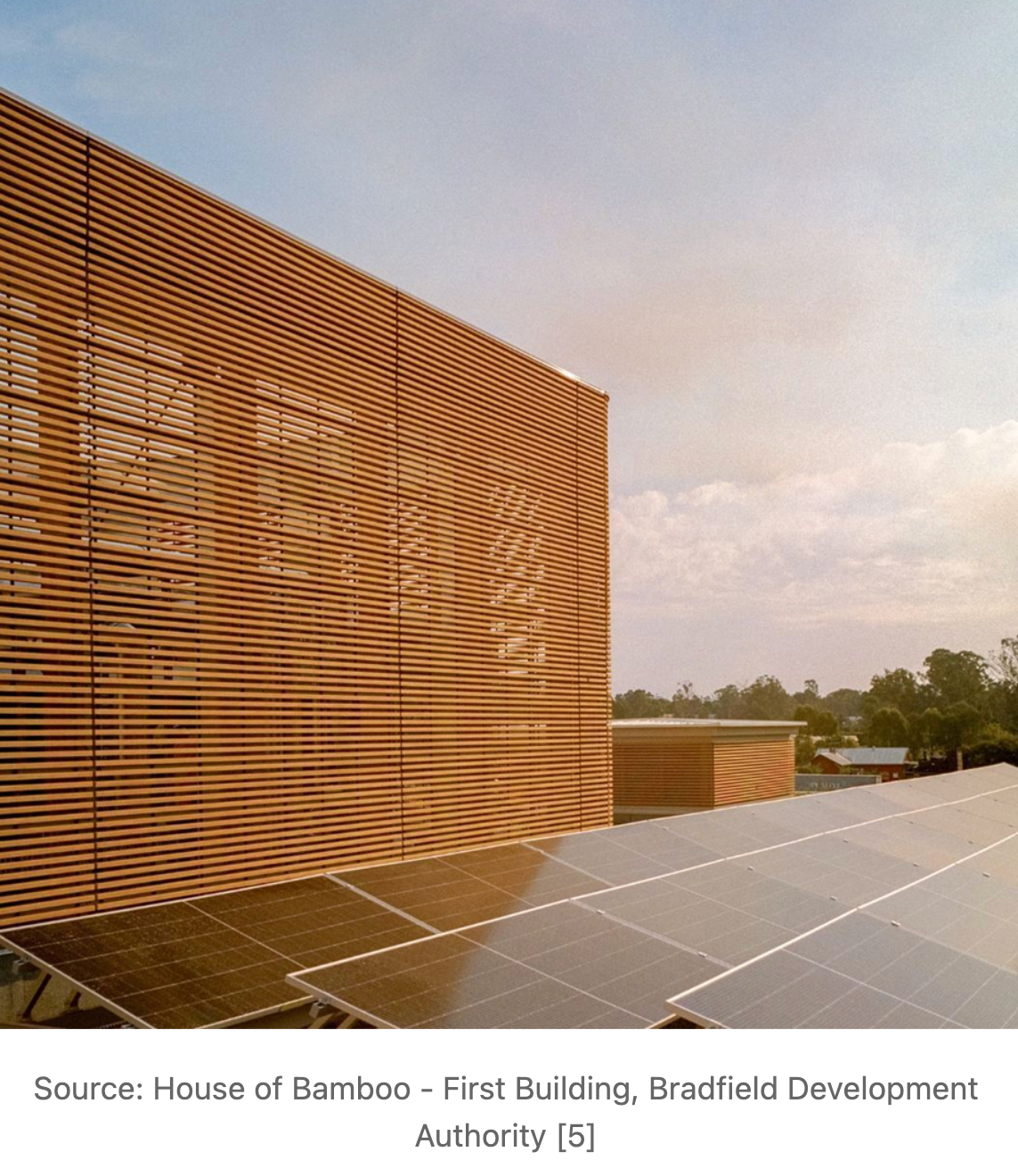

- First Building, Bradfield City Centre, Sydney (Hassell / Bradfield Development Authority, 2025), prefabricated timber frame + engineered bamboo battens and cladding + rammed-earth core. Embodied carbon <400 kg CO₂e/m². [5]

- Recent European Passivhaus and social-housing projects (2024–2025) — timber or glulam frames paired with straw or mycelium panels providing superior summer comfort, acoustics and circularity.[8] Examples include the EcoCocon Factory (UK, construction 2024–2025) using glulam frames with prefabricated straw panels for airtight, energy-positive walls; the award-winning Old Holloway Passivhaus (UK, referenced in 2025 awards) with timber-straw infill achieving 120% energy production via solar; and Scotland's social housing surge (e.g., Glasgow/Edinburgh prototypes) blending glulam with mycelium-enhanced straw for multi-unit acoustics.

Why “more of the same” won’t close the gap in Australia

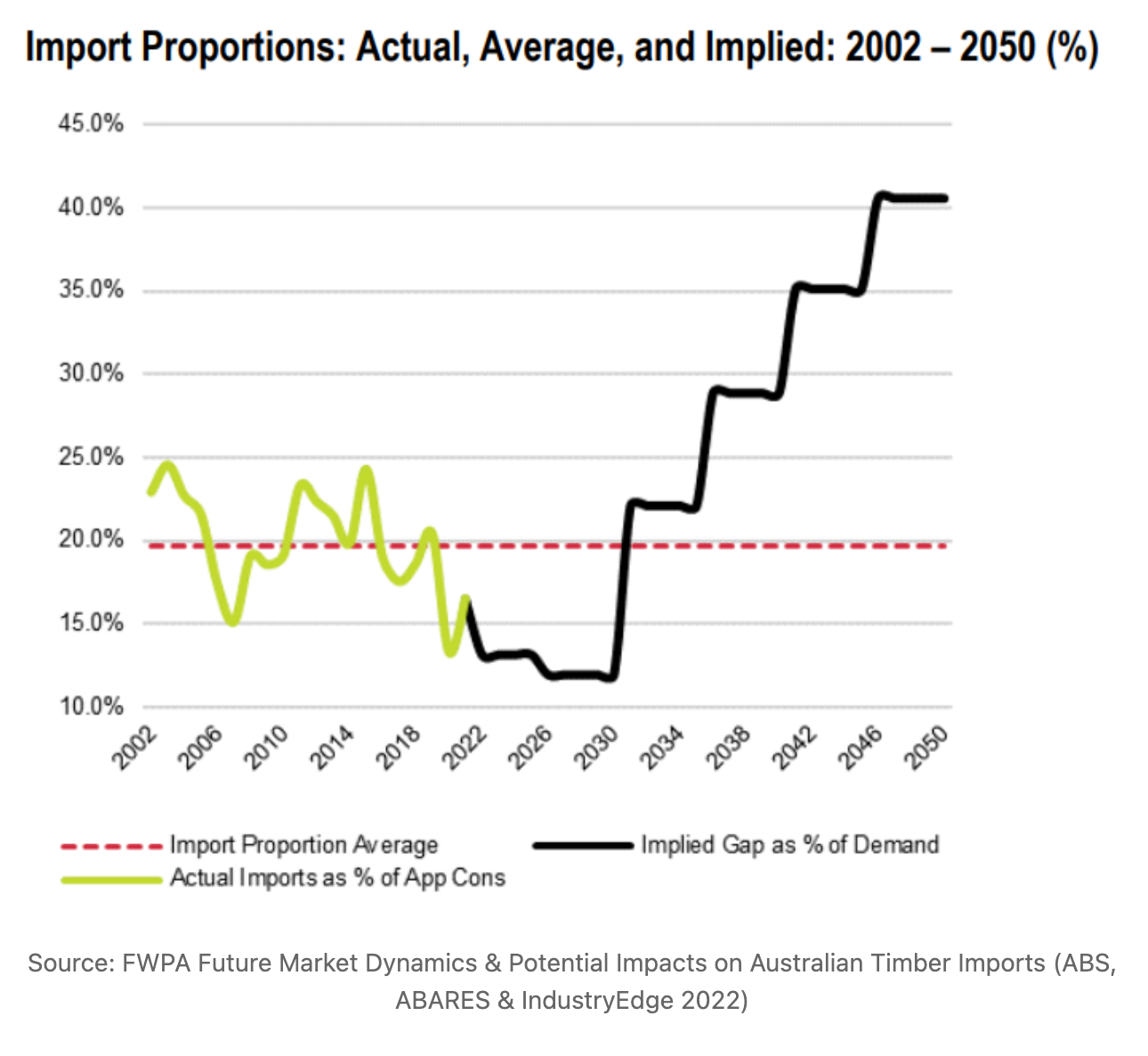

Domestic sawn softwood production is essentially static (or slightly declining after bushfire losses), while demand is forecast to rise from ~4.2 million m³ today to 6–6.5 million m³ by 2050, a 40–50% increase.[6] Imports, already close to 20% of supply in 2022 and rising, are projected to exceed 40% by mid-century, often from regions with different (and sometimes lower) certification standards than Australia’s certified plantations.[7]

FWPA Forecast 2002–2050: Actual sawn-softwood imports have hovered around 20% of supply (green line), but the implied gap needed to meet demand requires them to rise to 40.5% by 2050 (black line) — more than double today’s level. As the FWPA report notes [8 - at p50]: "By no later than 2031, the requirement for import supply will be permanently above the long-term average proportional contribution of imports. Notably, it is also the case that by no later than 2036, the requirement for import supply will be permanently above the long-term average actual import volume."

Simply planting more slow-growing pines cannot close this gap quickly enough. Fast-cycling biobased materials, engineered bamboo on marginal land, hempcrete from annual crops, straw and mycelium panels from existing agriculture, can deliver structural and semi-structural supply within 5–7 years, not 25–35. They are the necessary complement to plantation timber and, strategically, a powerful way for the timber industry itself to diversify its supply portfolio.

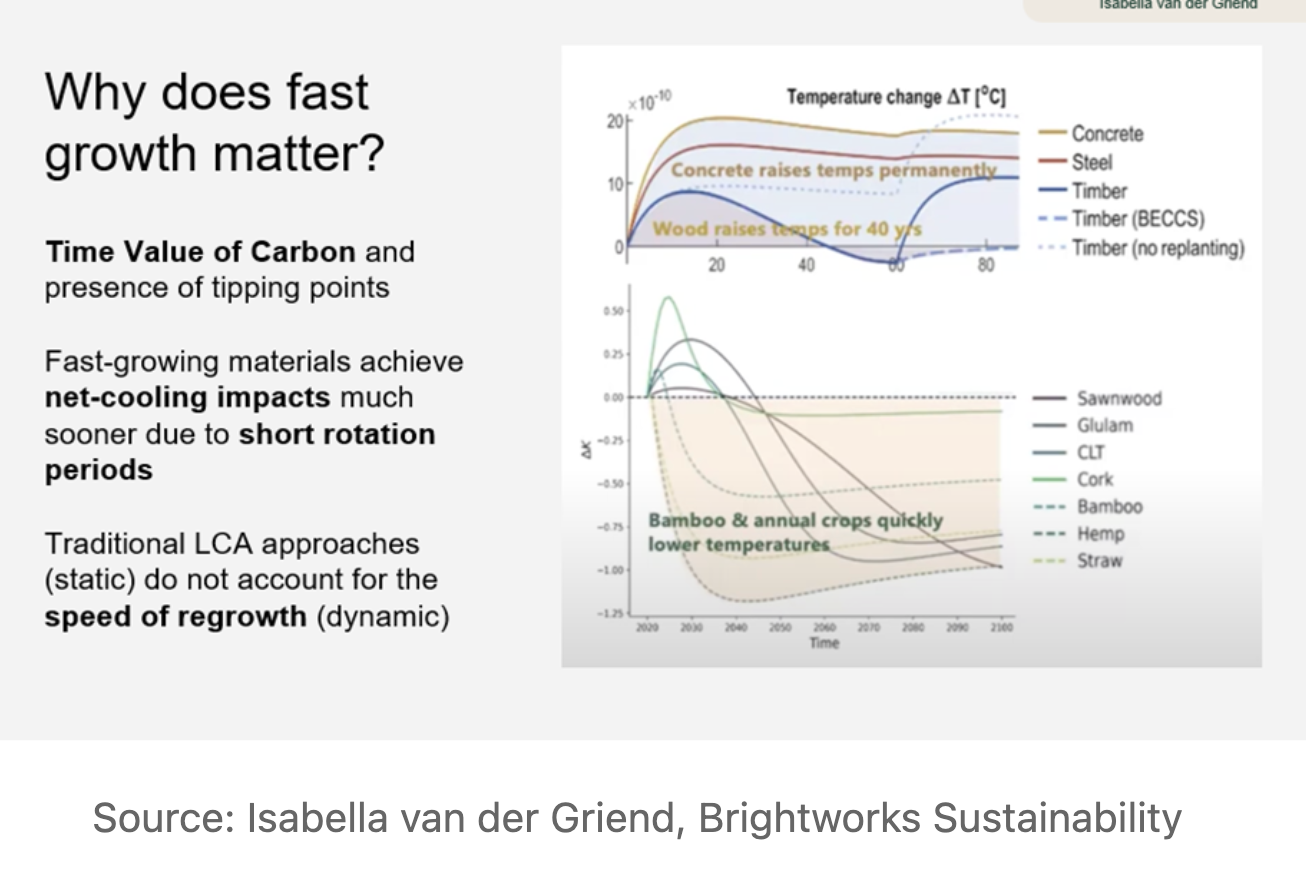

Carbon speed matters too

It’s not just about volume of timber; it’s about how quickly we can pull carbon out of the atmosphere when we are already in a climate emergency.

Plantation softwood is excellent at long-term storage, roughly 250 kg CO₂e per cubic metre locked away for decades once in a building.[9] But it takes 25–35 years to grow that cubic metre. That means the average annual sequestration rate on a pine plantation is only ~8–12 tonnes CO₂e per hectare per year. Crucially, radiata pine does not become a meaningful carbon sink until roughly year 7–9 after planting, and it only reaches its peak sequestration rate (25–40 t CO₂e/ha/yr) between about year 12–20. [14][15]

Fast-cycling biobased crops operate on an entirely different timescale:

- Industrial hemp removes 10–22 tonnes CO₂e/ha in just 100–120 days. When turned into hempcrete, every cubic metre is carbon-negative (−100 to −310 kg CO₂e) because the lime binder re-absorbs CO₂ as it cures.[10]

- Engineered bamboo (non-invasive clumping species) sequesters 35–50 tonnes CO₂e/ha/year during its 3–7 year growth phase — 3–5× higher than pine plantations, and the finished laminated bamboo stores ~300–350 kg CO₂e/m³.[11]

- Straw and agricultural-residue panels use by-products that would otherwise decompose or be burned, avoiding emissions and providing insulation with embodied carbon close to zero.[12]

- Mycelium composites are grown in days on waste substrates and routinely achieve −50 to −150 kg CO₂e/m² of panel across the lifecycle.[13]

In climate terms, this matters enormously. A hectare of hemp or bamboo removes as much CO₂ in one year as a pine plantation removes in three to five years. When we need drawdown now, not in 2050, the time value of that carbon is decisive.

Hybrid buildings that combine plantation timber frames with hempcrete infill, bamboo beams and straw/mycelium panels can reach net-negative embodied carbon (A1–A5) today, something almost impossible with timber-only systems once transport and processing are fully accounted for.

The supply-gap argument and the time-value-of-carbon argument point to the same conclusion: relying solely on slow-growing plantations leaves both volume and urgent decarbonisation targets at risk. Fast-cycling, high-sequestration biobased crops are not optional extras, they are the fastest, most powerful complement we have.

Most research and policy funding in Australia still flows almost entirely to long-rotation forestry solutions, perfectly good, but inherently slow. Almost none is directed at these fast-cycling agricultural crops that can deliver usable, low-carbon building products in months or a handful of years instead of decades. If we want both volume and rapid decarbonisation, that balance must change.

Time to work as a family

FWPA, Hemp Industry Australia, Bamboo Society of Australia, the Australian Straw Bale Building Association, mycelium researchers and allied groups don’t need a perfect slogan, they just need to start talking and collaborating now. Joint research, shared supply-chain mapping, combined trade displays and unified advocacy would carry far more weight than any single voice.

Plantation timber remains the big sibling for primary structure and long-term carbon storage. Its faster relatives, engineered bamboo for beams and framing, hempcrete for infill and insulation, straw and mycelium for panels, handle the jobs timber cannot do quickly or on certain land.

Together they give us greater supply security, fewer imports, and more productive hectares.

One ordinary Australian house wall in 2030 could be built like this:

- Plantation pine frame (25–35 years to grow)

- Laminated bamboo beams and large studs, grown in the wide rows between young pines or on the salty paddock next door (ready in 3–7 years)

- Hempcrete infill poured from last summer’s hemp crop

- Straw or mycelium insulation panels made from this season’s wheat stubble

Four everyday Australian crops. One wall. All grown here.

Jeremy Mansfield OAM is founder and director of Mansfield Advisory, supporting the transition to sustainable construction practices, supporting engineered bamboo industry development, nature-based construction materials and low-carbon building solutions for Australia.

References

[1] Arnel, T. (2025). We can't decarbonise construction if we demonise timber. The Fifth Estate. https://thefifthestate.com.au/columns/spinifex/we-cant-decarbonise-construction-if-we-demonise-timber/

[2] Future Market Insights. (2025). Bio-Based Building Materials Market | Global Market Analysis Report - 2035. https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/bio-based-building-materials-market

[3] Bio-based Industries Consortium (BIC). (2024). BIC Trend Report 2024-2025. https://biconsortium.eu/publication/bic-trend-report-2024-2025 (includes insights on fast-growing segments like bamboo, straw, and mycelium via Nova-Institute collaborations).

[4] Zhejiang University. (2024). Topping off of the first multi-story engineered bamboo building. https://www.zju.edu.cn/english/2024/0130/c19573a2876560/page.psp

[5] Bradfield Development Authority. (2025). First Building sets sustainable and resilient benchmark for Bradfield City Centre. https://www.nsw.gov.au/departments-and-agencies/bradfield-development-authority/news-and-updates/first-building-sets-sustainable-resilient-benchmark-for-bradfield-city-centre

[6] Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES). (2024). Australian forest and wood products statistics, September 2024. https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/research-topics/forests/forest-economics/forest-wood-products-statistics

[[7] Forest & Wood Products Australia (FWPA). (2022). Future Market Dynamics & Potential Impacts on Australian Timber Imports – Final Report. https://fwpa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/SAE179-2021_Future_market_dynamics__potential_impacts_on_Australian_timber_imports.pdf

[8] Passivhaus Trust. (2025). Exemplar Sustainable Building Awards 2025: EcoCocon Straw Panel Winner (covers Old Holloway, EcoCocon Factory, and Scottish social housing prototypes). https://www.passivhaustrust.org.uk/news/detail/?nId=1445

[9] Forest & Wood Products Australia (FWPA). (2023). Carbon storage in harvested wood products. https://www.fwpa.com.au/images/resources/Carbon_Storage_in_Harvested_Wood_Products_2023.pdf

[10] Arrigoni, A. et al. (2023). Life cycle assessment of hempcrete: A carbon-negative building material. Journal of Cleaner Production. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138247 (open-access summary: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095965262303619X)

[11] International Bamboo and Rattan Organisation (INBAR). (2024). Bamboo as a substitute for timber: Climate change mitigation potential. https://www.inbar.int/resources/inbar_publications/bamboo-as-a-substitute-for-timber/

[12] EcoCocon & Passivhaus Trust. (2024). Life-cycle carbon assessment of straw-based building systems. https://www.passivhaustrust.org.uk/UserFiles/File/Tech/EcoCocon_Straw_LCA_2024.pdf

[13] Mycelium Materials Europe & Nova-Institute. (2025). Life Cycle Assessment of Mycelium Composites 2025. https://nova-institute.eu/pub/lca-mycelium-composites-2025/

[14] Paul, K.I. et al. (2019). Carbon sequestration in Australian plantation forests. CSIRO / Dept of Agriculture. https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/carbon-sequestration-australian-plantation-forests.pdf

[15] Scion (2023). Carbon sequestration rates for Pinus radiata in Australia and New Zealand. https://www.scionresearch.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/86472/Carbon-sequestration-rates-for-Pinus-radiata.pdf