Blind Spots on the Road to Net-Zero: Australia’s Refrigerant Reporting Gaps

Introduction

Australia’s National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) Act mandates that large corporations report greenhouse gas emissions, energy production, and consumption, including emissions from refrigerants. Refrigerants, such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), are potent greenhouse gases with high global warming potential (GWP), making their accurate tracking vital for meeting national climate targets. Yet, the NGER framework has significant flaws—exemptions for small air conditioning units or refrigerants with a GWP ≤1,000, reliance on estimated data, absence of leakage registers, and unreported end-of-life emissions—that likely result in underreported emissions. Starting January 1, 2025, the Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards (ASRS) will introduce broader climate-related disclosures, but these new rules are unlikely to fix the specific gaps in refrigerant reporting. This article explores these issues, compares Australia’s approach to international practices, and proposes improvements to keep the country on track for net-zero.

Regulatory Frameworks and Their Limitations

Australia’s refrigerant management involves multiple frameworks with distinct roles. The Ozone Protection and Synthetic Greenhouse Gas Management Act (OPSGGMA) regulates the supply of refrigerants like HFCs through import quotas and licensing, using GWP values from the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report (AR4). A key example is its import restrictions on certain air conditioning equipment using refrigerants with a GWP over 750. These restrictions apply to:

Small systems—such as portable units, window/wall units, and non-ducted split systems with a refrigerant charge up to 2.6 kg—starting 1 July 2024, and

Multi-head split systems, including variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems, from 1 July 2025.

While these measures aim to curb the use of high-GWP refrigerants, they reveal a limitation: the emphasis is on controlling supply rather than tracking actual emissions outcomes. Frameworks like the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) Act and Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards (ASRS) depend on estimates rather than precise measurements, potentially overlooking emissions from systems not subject to these import bans.

Additionally, the reliance on AR4 GWP values introduces further gaps. For instance, R-32 has an AR4 GWP of 675, falling below the 750 threshold and thus remaining permissible in regulated systems. However, the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) updates its GWP to 771—above the threshold—suggesting that its climate impact may be underestimated. This discrepancy means that systems using R-32 could evade stricter controls, compounding the challenge of accurately reporting refrigerant emissions. Together, these factors highlight a blind spot in Australia’s approach, where supply-side restrictions and outdated metrics leave the full extent of refrigerant emissions unaddressed.

Why It Matters

According to Cold Hard Facts 4 [1], Australia holds about 55,000 tonnes of refrigerants—mostly HFCs—in systems nationwide, equivalent to 100 million tonnes of CO₂ if released. Only around 400-500 tonnes are being destroyed annually[1]. Refrigerants are a significant emissions source in the built environment, including residential and commercial buildings.

Blind Spots on the Road to Net-Zero: Australia’s Refrigerant Reporting Gaps

Our Upfront Opportunity: Australia’s Policy Roadmap to Reduce Upfront Embodied Carbon in the Built Environment by the Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council (ASBEC) [7]

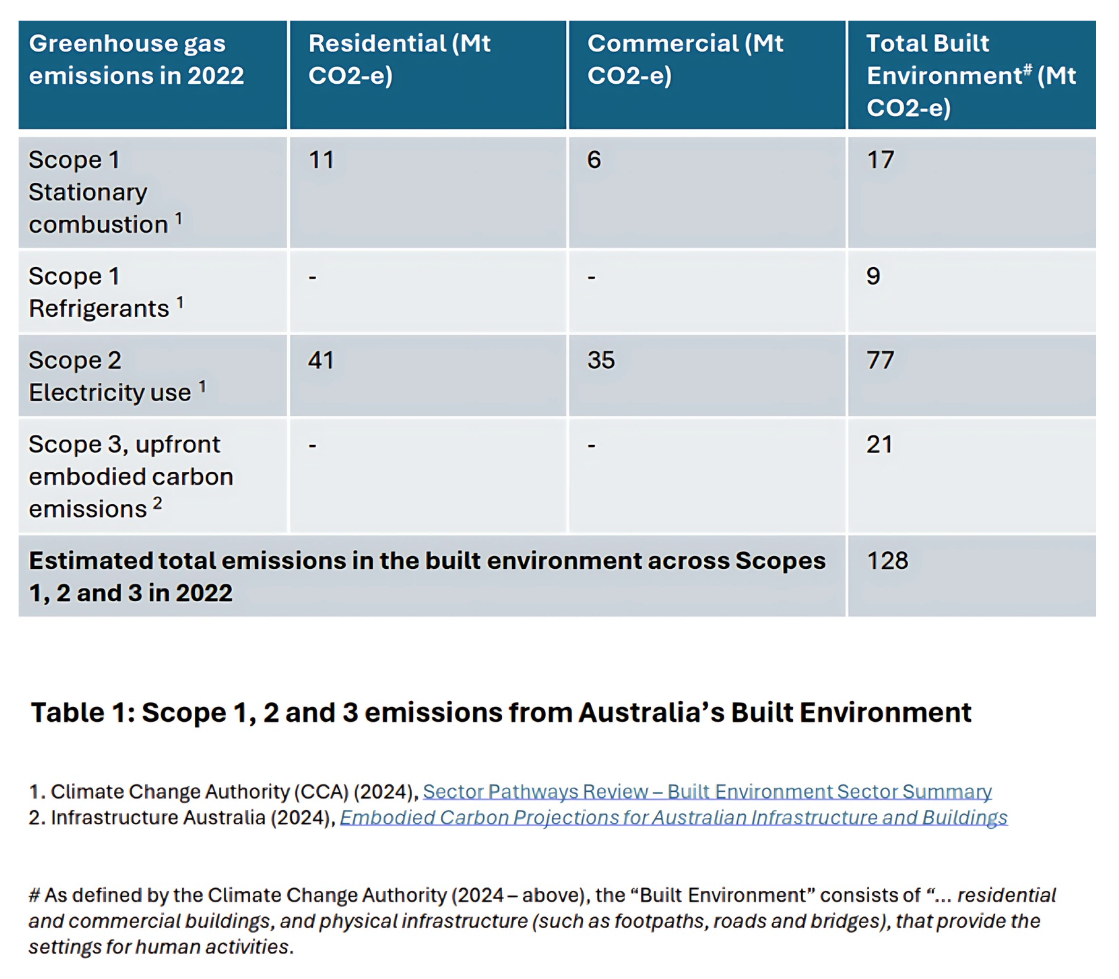

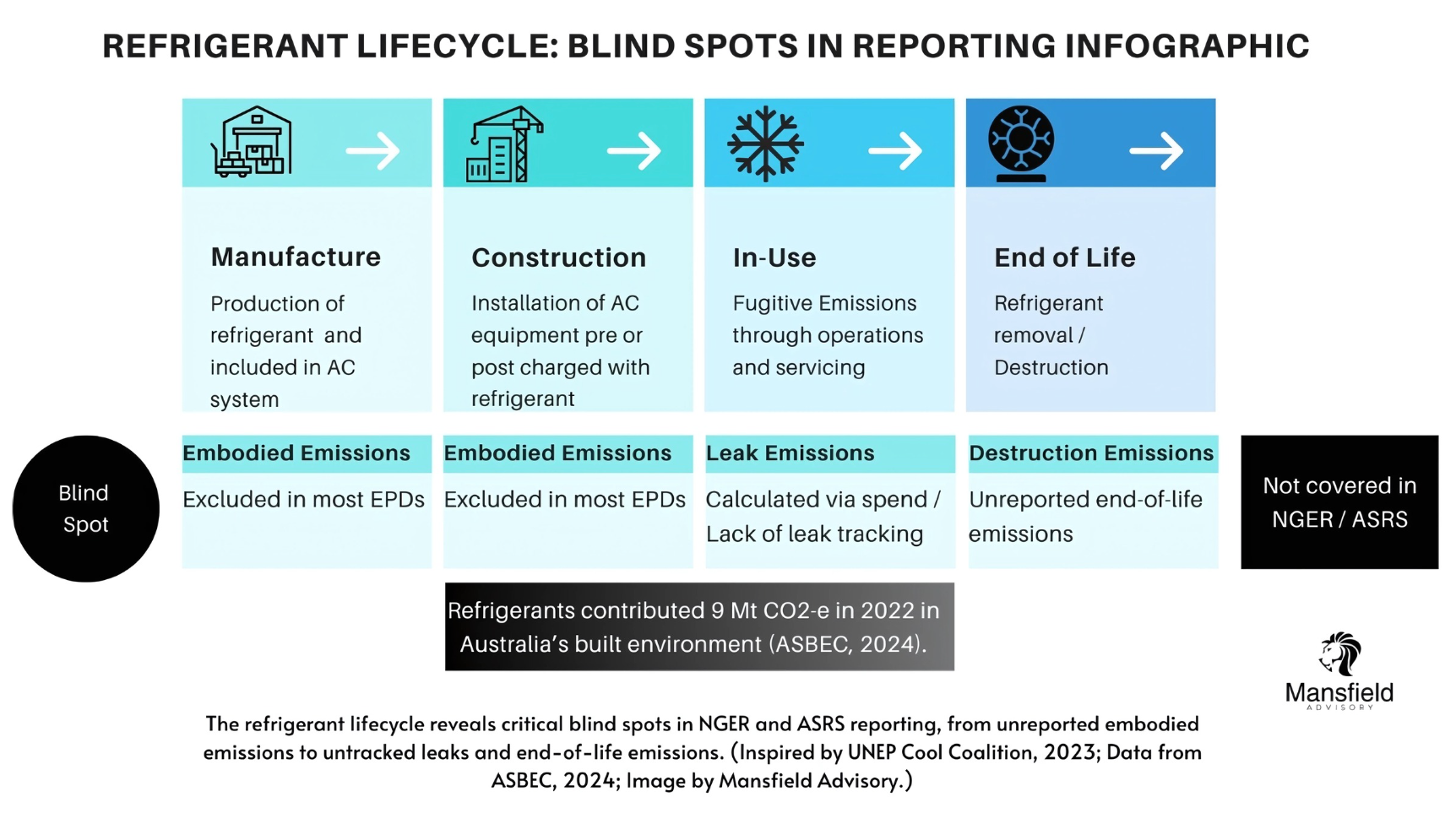

The Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council (ASBEC) reports that refrigerants contributed 9 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent (Mt CO2-e) emissions in 2022 across Scopes 1, 2, and 3 in the built environment (in operational use), out of a total 128 Mt CO2-e (ASBEC, 2024). This highlights their role in Scope 1 (direct) emissions, particularly from heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and refrigeration (HVAC&R) systems. This does not account for the significant refrigerant lifecycle emissions outside of operational use.

Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions from Australia's Built Environment. Source: ASBEC [7]

While energy efficiency improvements in buildings are a key strategy for reducing operational emissions, refrigerant leaks can significantly undermine these gains. For instance, a leak of HFC-134a, with a GWP of 1,430 (AR4; 1,530 in AR6), can offset the carbon savings achieved through energy-efficient systems, effectively wiping out progress.

Typical plant room for commercial building. Source: A.G. Coombs

More critically, Australia has key blind spots in tackling refrigerant emissions due to gaps in the NGER framework and its disconnect with OPSGGMA’s supply-focused approach. Without accurate data on leaks at a business level—despite some national insight from import reporting—the real impact on Australia’s net-zero trajectory remains unclear, hindering effective action. We cannot afford to rely on guesstimates for decades, as this risks delaying action on a significant emissions source.

Identified Issues in NGER Refrigerant Reporting

The NGER scheme’s approach to refrigerant emissions has several critical weaknesses:

- Exclusion of Smaller Systems or Lower-GWP Refrigerants: Systems with less than 100kg of refrigerant or using refrigerants with a GWP ≤1,000—common in retail and hospitality—are exempt, missing their cumulative emissions. For example, a system using R-32 (GWP 771 in AR6) is excluded due to its GWP, despite its growing use and climate impact, potentially missing significant cumulative emissions. A broad range of systems fit into this category.

- Reliance on Estimated Values: Default leakage rates, such as those for HFC-134a, replace actual measurements, risking inaccurate emissions estimates.

- Lack of Mandatory Leakage Registers: Unlike some overseas regulations, which mandate leak checks and records, NGER lacks systematic tracking, so emissions may be underreported or missed.

- End-of-Life Emissions Unreported: Emissions from the decommissioning and disposal of refrigerant systems are not tracked under NGER or ASRS reporting, though OPSGGMA includes measures to manage these processes.

New ASRS Reporting Requirements and Their Impact on Refrigerant Reporting

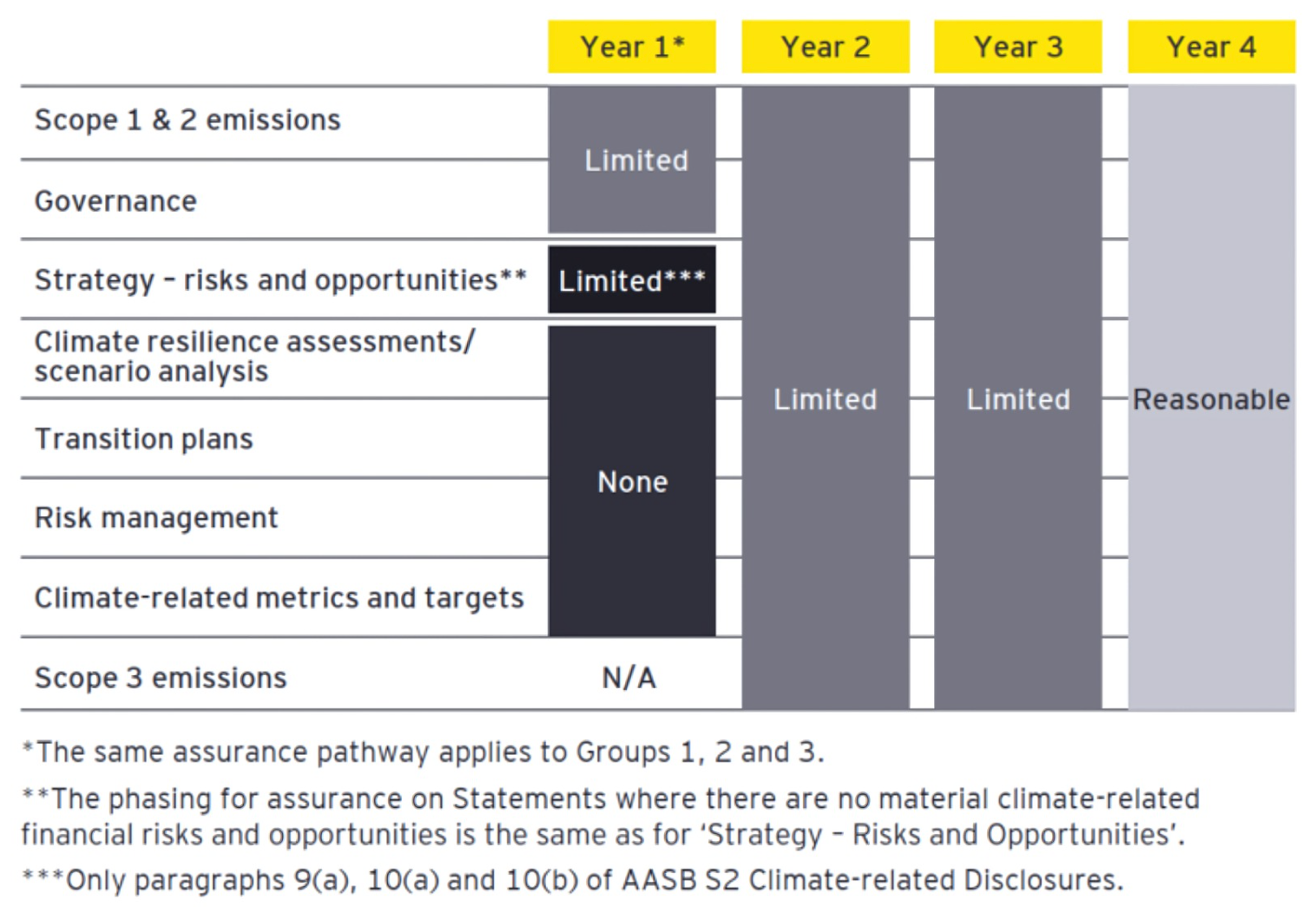

From January 1, 2025, the Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards (ASRS) have been issued by the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) and mandate climate-related financial disclosures, including:

Scope 1 emissions (direct emissions, including refrigerants),

Scope 2 emissions (indirect emissions from purchased energy), and

Scope 3 emissions (other indirect emissions, such as value chain impacts), phased in over time.

The ASRS applies to entities based on size and employee numbers, divided into three groups:

Group 1: Largest entities and significant emitters, starting January 1, 2025.

Group 2: Medium-sized entities, starting July 1, 2026.

Group 3: Smaller entities, starting July 1, 2027.

Source: EY [8]

Although ASRS broadens emissions reporting, it does not directly tackle NGER’s refrigerant-specific gaps:

Persistent Exclusions: ASRS does not address minimum unit sizes or the GWP >1,000 threshold, leaving smaller systems and low-GWP refrigerants potentially unreported.

Scope 3 and End-of-Life Emissions: Scope 3 reporting might eventually cover some end-of-life impacts starting in 2026 for Group 1, but this depends on implementation details and may not fully address in-use leaks or small systems.

Methodological Flexibility: ASRS allows entities to select emissions measurement methods, likely perpetuating reliance on estimates rather than actual data.

Since NGER and ASRS will coexist, entities must comply with both, but ASRS does not inherently resolve NGER’s refrigerant reporting deficiencies. Recent ASIC’s guidance may also exacerbate these gaps by prioritising practicality over precision in the early stages of implementation.

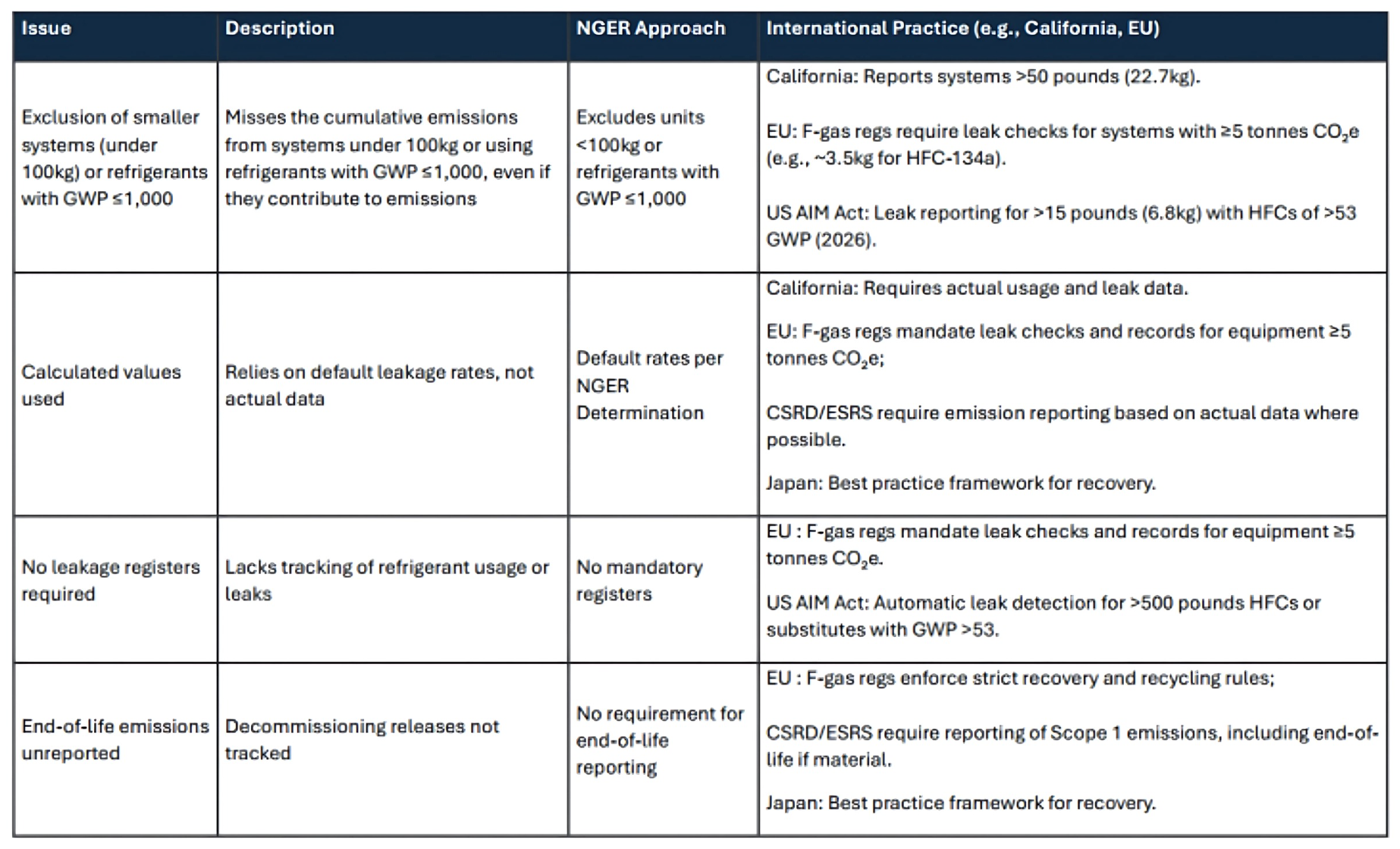

Table: Summary of Issues and International Comparison

The table below summarises the five key issues and compares NGER’s approach with some examples of international best practice from US, California, Japan and the European Union (EU):

Summary of Issues and International Comparison

This comparison highlights that NGER falls short of international benchmarks, and ASRS does not yet adopt these best practices to bridge the gaps. To address these shortcomings, targeted improvements are needed.

Opportunities for Improvement

Despite ASRS’s broader scope, NGER’s persistent gaps call for targeted enhancements in refrigerant emissions reporting:

Cumulative Thresholds: Introduce a facility-wide refrigerant reporting threshold that accounts for the total refrigerant use across all systems, capturing emissions from numerous small, distributed systems—like those in retail or hospitality—that are currently exempt but collectively contribute to significant emissions.

Lower GWP Limits: Remove the GWP >1,000 threshold to include refrigerants like R-32 under both frameworks.

Actual Data Mandates: Require actual usage and leakage data to replace estimates and ensure accurate reductions.

Mandatory Leakage Registers: Enforce detailed records of refrigerant usage and leaks, aligning with California and EU standards.

End-of-Life Reporting: Mandate end-of-life emissions reporting under NGER and ASRS for comprehensive tracking.

These changes could build on ASRS’s expanded reach but would require regulatory updates to be effective. By phasing in requirements and providing support (e.g., templates, incentives, pilot programs), Australia could improve data quality without overwhelming reporting entities, ensuring we don’t perpetuate guesstimates for decades while still moving toward net-zero. Collaboration with industry partners will be key to implementing these solutions, ensuring businesses can accurately monitor and manage emissions to support Australia’s net-zero goals.

Conclusion

Australia’s refrigerant reporting frameworks—NGER and ASRS—harbor critical blind spots that conceal the true extent of emissions, derailing the nation’s net-zero ambitions. Exemptions for small units or refrigerants with GWP ≤1,000, reliance on estimates, missing leakage registers, and untracked end-of-life emissions persist even with ASRS’s broader requirements, leaving significant gaps unaddressed. These blind spots hinder accurate emissions tracking and risk providing a clear view of the refrigerant challenge. To eliminate these oversights and stay on the road to net-zero, Australia should transition to actual data collection, align with international best practices, and close these gaps decisively.

Thanks to Adrian Bukmanis, Veridien Refrigerant Management, for his expert input and review.

Note: GWP values used in this article use AR6 for scientific accuracy (e.g., HFC-134a at 1,530), while NGER uses AR4 (e.g., HFC-134a at 1,430), which may underestimate impacts.

Other articles in this refrigerant series you may have missed:

Article 1 - Could Australia become a dumping ground for refrigerants?

Article 2 - How is New Zealand tackling refrigerants, and are there lessons for Australia?

REFERENCES

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. (2023). Cold Hard Facts 4. DCCEEW. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/publications/cold-hard-facts-4

Clean Energy Regulator. (2022). National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Measurement) Determination 2008. Australian Government. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2022C00815

California Air Resources Board. (2021). Refrigerant Management Program. CARB. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/refrigerant-management-program

European Commission. (2014). Regulation (EU) No 517/2014 on fluorinated greenhouse gases. European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014R0517

United Nations Environment Programme. (2020). Global Refrigerant Management Initiative. UNEP. https://www.unep.org/ozonaction/resources/publications/global-refrigerant-management-initiative

Australian Government. (2024). Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards (ASRS). Australian Government. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2024L00001

Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council. (2024). Our Upfront Opportunity: Australia’s Policy Roadmap to Reduce Upfront Embodied Carbon in the Built Environment. ASBEC. https://www.asbec.asn.au/research-items/our-upfront-opportunity-australias-policy-roadmap-to-reduce-upfront-embodied-carbon-in-the-built-environment/

EY. (2025). Mandatory Climate-Related Financial Disclosures: What You Need to Know. EY. https://www.ey.com/content/dam/ey-unified-site/ey-com/aus-rzl/documents/pdfs/mandatory-climate-related-financial-disclosures-what-you-need-to-know.pdf

Tilbury, J. (2025). Unpacking ASIC’s Regulatory Guide on Sustainability. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/unpacking-asics-regulatory-guide-sustainability-james-tilbury-k6wxc

First published on

LinkedIn 9th April 2025