Could Australia Become A Dumping Ground for Refrigerants?

Mansfield Advisory Pty Ltd

First published on LinkedIn - October 17, 2024

In Australia, cooling is a year-round necessity, attributed to both the harsh summer temperatures and the continuous operation of commercial refrigeration. This sustained demand has put the refrigerant industry in the spotlight, where it must balance environmental considerations and regulatory requirements. The challenges with refrigerants are not limited to the warmer months but are indicative of Australia's extensive reliance on cooling across various sectors. Further complicating this issue are the global shifts towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions, compelling the industry to adopt more sustainable practices while still fulfilling the need for efficient cooling. This situation is exacerbated by the global phase-out of high Global Warming Potential (GWP) refrigerants, which could make countries with less stringent regulations vulnerable to becoming dumping grounds for less desirable refrigerants.

Environmental and Health Consequences

"The Hot Reality: The Urgent Need for Sustainable Cooling" report by the Centre For Sustainable Cooling indicates a potential 90% increase in global cooling-related electricity consumption by 2050, underscoring cooling's significant role in energy demand and climate change. Cooling processes alone contribute to 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with projections suggesting these could double by 2030 or even triple by 2100. ColdHardFacts4 identified that refrigeration and air conditioning equipment contribute about 12% of Australia's total GHG emissions. According to Cold Hard Facts 4, direct emissions represent 11% of total emissions from RAC equipment, end-of-life is about 8%, and indirect emissions represent 81%. Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), widely used in cooling systems, have high Global Warming Potential (GWP) and are the fastest-growing source of greenhouse gas emissions globally due to the rising demand for space cooling and refrigeration.

Parallel concerns exist with per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), known for their persistence in the environment and potential health risks, earning the nickname "forever chemicals." These substances further complicate the environmental footprint of cooling technologies. Once released, they do not break down easily and can accumulate in the environment and living organisms, leading to widespread contamination.

From a health perspective, exposure to PFAS has been linked to numerous adverse effects. According to research findings, these include liver damage, thyroid disease, decreased fertility, high cholesterol, obesity, and even cancer. These chemicals can enter the human body through contaminated water, food, or air, and once inside, they can affect various bodily systems. The concern about PFAS is not just about their direct impact but also their ability to bioaccumulate, meaning levels can build up over time in the body and the environment, leading to increased health risks from prolonged exposure.

Refrigerants and Scope 1 Emissions

Scope 1 emissions are direct greenhouse gas emissions from sources owned or controlled by a company. In the context of refrigerants, these are primarily fugitive emissions: leaks from refrigeration and air conditioning systems during operation, maintenance, or at the end of life. Despite their direct impact, these emissions are often overlooked in the broader discussion of greenhouse gases but are pivotal in Australia's fight against climate change.

Mandatory Emissions Reporting: Australia's New Framework

Australia's introduction of mandatory disclosure from 1st January 2025 for Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions places refrigerant management under a microscope:

- Scope 1: Companies must now meticulously track and report refrigerant leaks, pushing for better containment and the use of refrigerants with lower Global Warming Potential (GWP).

- Scope 2 & 3: While Scope 2 involves indirect emissions from purchased energy, Scope 3 includes all other indirect emissions in a company's value chain, which could involve emissions from refrigerant production, disposal, and products sold to consumers.

The Global Battle Against Illicit Refrigerant Trade

Setting the Scene:

The global community has increasingly recognized the environmental threat posed by hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), leading to significant international agreements and national policies to curb their use. The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol is a pivotal moment where nations committed to phasing down HFCs to mitigate climate change. This amendment has spurred countries into action, each implementing various measures to meet their reduction targets:

- Europe has advanced its F-gas Regulation, aiming to reduce F-gas emissions through quotas, bans on certain products, and stricter leakage checks.

- In the United States, the American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act directs the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to address HFCs by phasing down their production and consumption, promoting alternatives, and managing existing stocks.

- Australia has its own HFC phase-down strategy, part of its broader commitment under the Kigali Amendment, which involves reducing the availability of HFCs through a quota system.

The introduction of caps on HFC quotas globally has unintentionally laid the groundwork for an illicit trade. As legal supplies dwindle and prices rise due to scarcity, the black market for these potent greenhouse gases thrives. Smugglers exploit the price differential and the slower phase-out schedules in some countries, turning regions with less stringent controls into potential dumping grounds for illegal HFCs.

This scenario not only undermines global efforts to combat climate change but also poses significant challenges for law enforcement and regulatory bodies worldwide, as they strive to enforce compliance with international environmental agreements while battling the economic allure of the black market in refrigerants.

Recent events and actions:

- United States: Enforcement has become more rigorous with the introduction of the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act (AIM Act), which has led to the first prosecution of illegal HFC importation in 2024. This case underlines the U.S.'s commitment to curb the black market for these substances, highlighting the lucrative nature of HFC smuggling, comparable in profitability to the historical smuggling of substances like CFCs. Update: In March 2025, a 57-year-old CEO from Georgia, USA, was charged with violating the American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act. He allegedly imported 500 cylinders of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) from Peru without proper authorization. This marks the second prosecution under the AIM Act in the U.S., signaling increased enforcement against illegal HFC imports as part of the phasedown efforts.

- European Union: Despite having stringent regulations, the EU faces challenges with illegal HFCs primarily entering through Bulgaria from Turkey and China. The EIA has pointed out ongoing issues, with Romania and Bulgaria as key entry points. Smugglers employ sophisticated methods like mislabelling and exploiting corruption to bypass enforcement.

- Enforcement Actions: Significant seizures have occurred, like in the Netherlands and Italy, where large quantities (40 tonnes in both instances) of illegal refrigerants were intercepted. These actions demonstrate the scale of the illegal trade and the efforts to combat it. Update: More recently, a thousand cylinders containing around 14 tonnes of illegal HFC were seized in Italy (March 2025),

- Adaptation of Criminal Networks: Criminals adapt quickly to enforcement measures by altering their strategies, such as changing labels or using disposable containers to make detection harder. Spain has become a hotspot for online sales of illegal HFCs, showcasing the adaptability and reach of these networks. Update: Romania, a key backdoor for illegal refrigerants in Europe, uncovered a cross-border smuggling network in February 2025. Operating along the Turkey-EU route for years, this syndicate even supplied customs with testing technology to detect their own imports.

- Global Crackdown: These activities are part of a broader global crackdown influenced by international agreements like the Montreal Protocol and its Kigali Amendment, which aim to phase down HFCs to mitigate climate change. The Kigali Amendment, which came into force on January 1, 2019, specifically targets the phase-down of HFCs, recognizing them as potent contributors to climate change. The amendment has seen ratification from 160 states as of July 1, 2024, plus the European Union, indicating strong, though not yet universal, international support for reducing HFC use. The involvement of various countries indicates a widespread recognition of the problem but also underscores the challenges in enforcement due to differing phase-out schedules and economic incentives for illegal trade.

- Challenges and Persistence: Despite efforts, illegal trade persists due to high profits and varying international regulations, which create loopholes exploited by organized crime. The EIA's April 2024 report suggests that while steps are being taken, the illegal trade in HFCs remains a dynamic and persistent issue, adapting to new regulations and enforcement tactics.

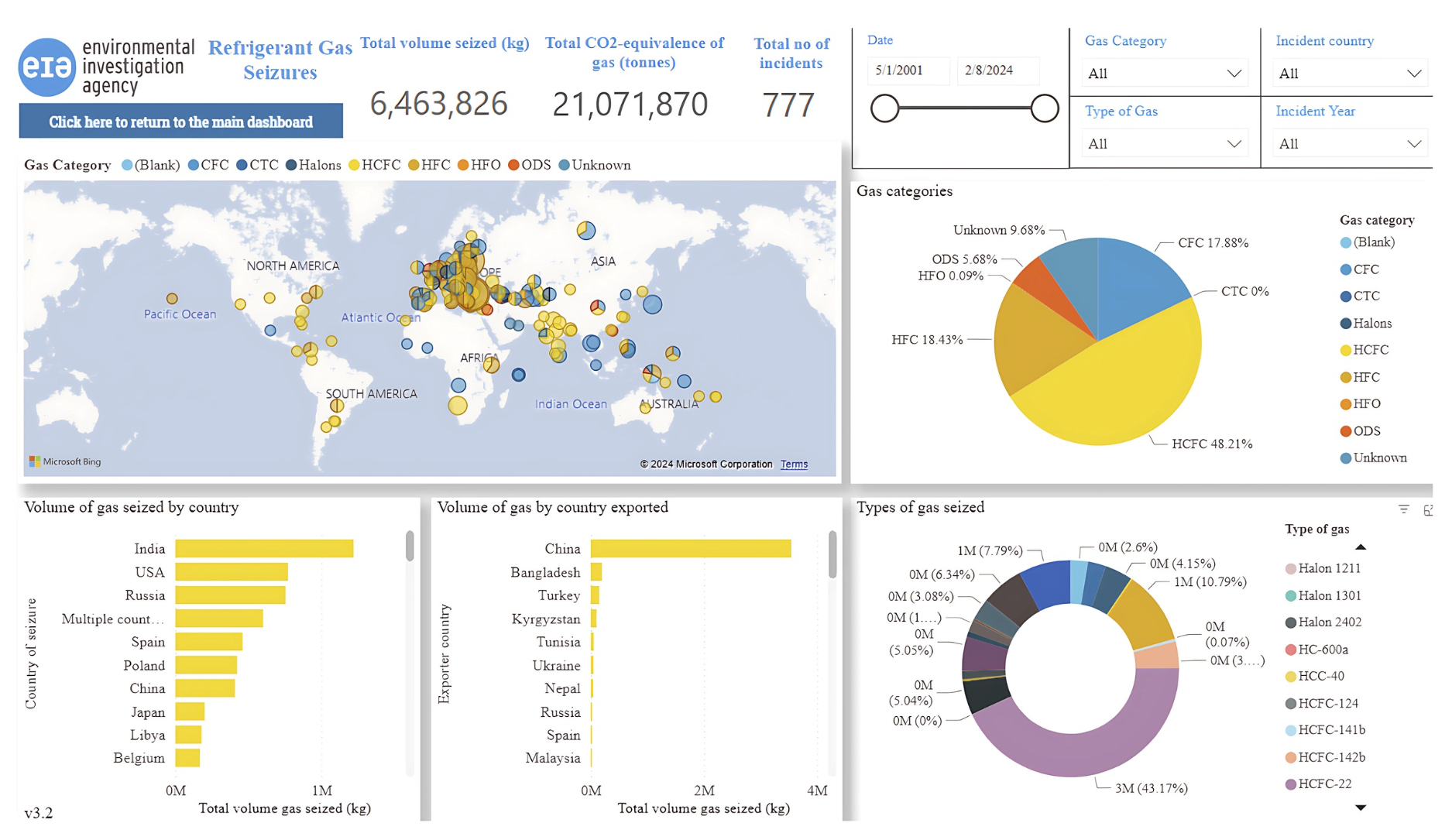

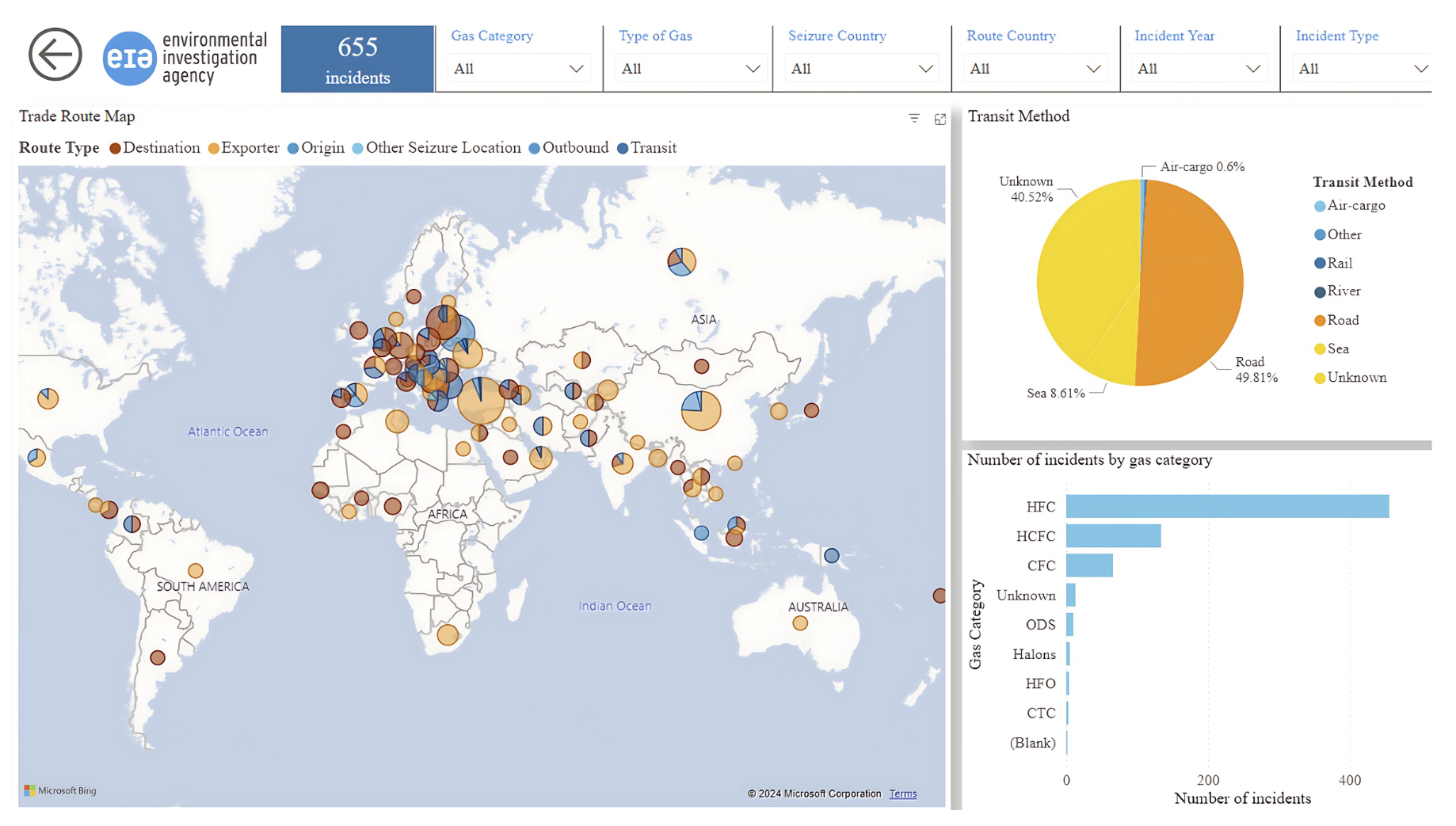

The Environmental Investigation Agency's dashboard serves as a tool for monitoring the illicit trade in refrigerants, providing a comprehensive overview of the extent and dynamics of this underground market.

EIA tracking dashboard

Total volumes of refrigerant gas seizures

Total number of incidents

Australia's Vulnerability to Refrigerant Market Challenges

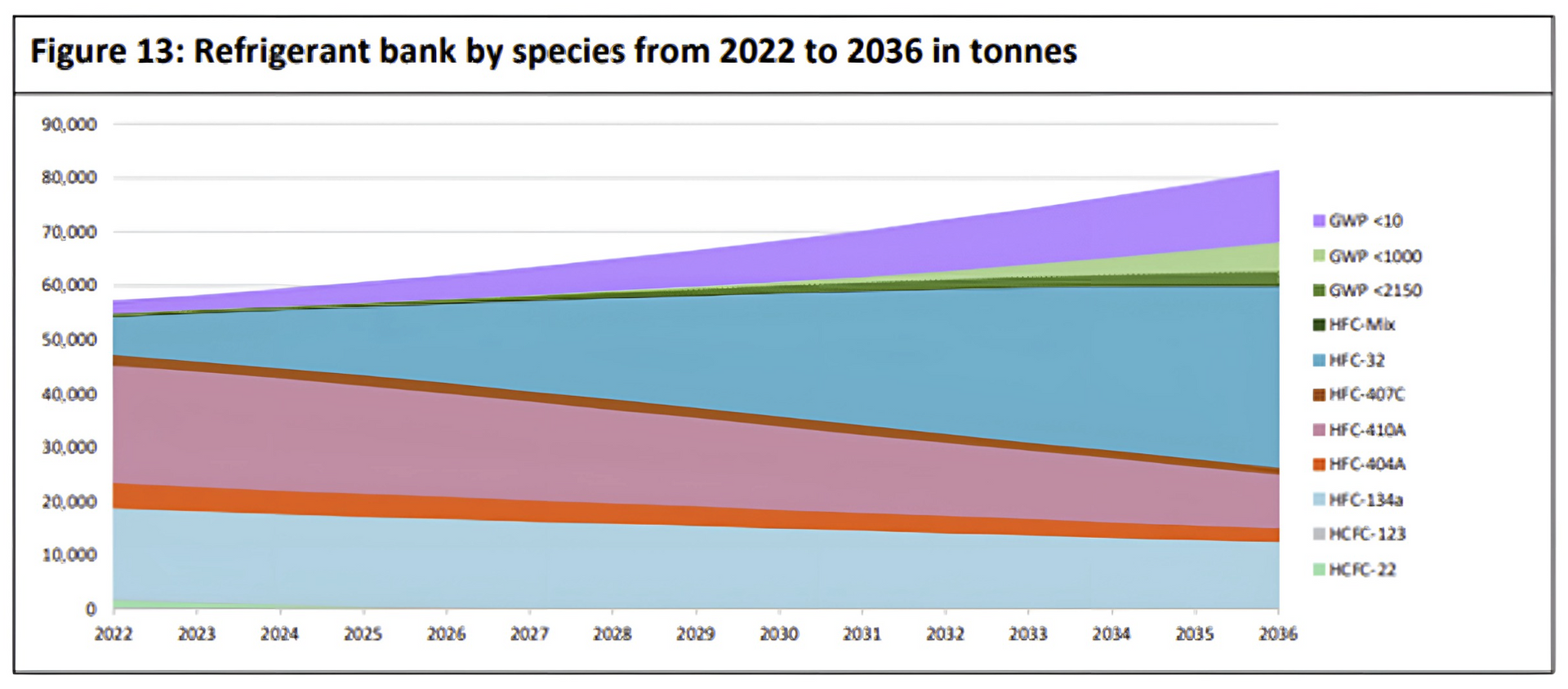

Australia's involvement in this illicit market isn't just as a bystander but potentially as a victim of illegal trade. The Cold Hard Facts4 study underscores Australia's refrigerant market dynamics, predicting growth using controlled and natural refrigerants. The ColdHardFacts4 forecasts that HFC-32 will still account for 70% of sales in Australia by 2036. However, the global push towards lower GWP alternatives and the illegal trade dynamics could see Australia becoming a target for cheap, high-GWP refrigerant dumping. This not only undermines Australia's environmental commitments under international agreements like the Kigali Amendment but also poses economic challenges by undercutting legitimate businesses with illegally sourced, cheaper alternatives.

According to Cold Hard Facts4, the total bank of controlled refrigerants in 2022 was estimated at approximately 55,027 metric tonnes and is expected to expand by more than 13% to approximately 62,200 metric tonnes (81,300 metric tonnes, including HFOs and natural refrigerants) in the 14-year period of the projections from 2022 to 2036. The emergence of heat pumps substituting for gas appliances is the biggest driver of growth for HFCs in the bank over the next decade.

Refrigerant bank by type (ColdHardFacts4, DCCEEW 2024)

The federal government has amended (June 2024) the Ozone Protection and Synthetic Greenhouse Gas Management Regulations to ban the import and manufacture of small air conditioning systems using high-GWP refrigerants (i.e. R410A - GWP of 2088 and R134a - GWP of 1430, for systems with <2.6kg of refrigerant charge). The updates also introduce new penalties for offences under the regulations, albeit the imposed maximum penalty of 60 units is not much of a deterrent.

Economic and Environmental Ramifications

The influx of illegal refrigerants could distort the market, leading to unfair competition and potentially stalling the adoption of environmentally friendlier technologies. On the environmental front, introducing these substances could significantly hinder Australia's efforts to reduce its carbon footprint, given the high GWP of illegally traded HFCs.

Debating the Pace of Refrigerant Phase-Down

While there are legitimate concerns that a rapid phase-down of refrigerants could spur illicit trade, there's a counterargument to be considered. Prolonging the transition away from these substances might widen the opportunity for illegal activities. This is because an extended demand period for outdated technology could continue to fuel the black market for longer than necessary.

The Threat of Refrigerant Dumping

As a result of being behind the EU and the US with restrictions in product categories, the market opportunity means older products (such as R410A with a GWP of 2088 in large VRV systems) are likely to be dumped into Australia. It poses both an environmental risk and a market distortion issue. This phenomenon could lead to:

- Environmental Impact: Continued use of higher GWP refrigerants delays the transition to more environmentally friendly alternatives, extending the environmental footprint of these substances.

- Market Dynamics: The influx of older, less efficient technology can hinder the adoption of new, more efficient, and less harmful technologies, affecting market evolution towards sustainability.

Customs authorities intercepted over 40 tonnes of illegal HFC refrigerant at the port of Gioia Tauro, Italy (August 2024).

Uncontrolled refrigerant consumption

Although a ban has now been placed on small AC units containing high-GWP refrigerants such as R410A and R134a, the Government is yet to restrict the import of other classes of pre-charged equipment containing high-GWP refrigerant. This means that Australia is not properly controlling refrigerant consumption, which undermines the phase-down efforts by not addressing the full lifecycle of refrigerant-containing products.

Strategies for Regulation and Innovation

To prevent potential issues with the illicit refrigerant trade, Australia could consider strengthening its regulatory measures. This includes improving border surveillance, revising penalties to deter smuggling better, and addressing gaps in regulations that allow pre-charged equipment to bypass current quotas. Implementing a more rigorous tracking system for the refrigerant lifecycle, from production through disposal, could also help mitigate illegal trade activities.

International cooperation is vital; Australia should align its refrigerant phase-down schedules with global leaders like the EU to minimize opportunities for refrigerant dumping.

On the innovation front, promoting the adoption of natural refrigerants like propane (HC-290) through incentives and research could accelerate the shift from high-GWP alternatives, reducing the market for illicit refrigerants while addressing environmental concerns and safety considerations.

Capitalizing on the Transition to Sustainable Cooling

Australia is at a defining moment where its approach to refrigerant regulation could lead the way in global sustainability efforts. Businesses are now tasked with navigating the complexities of mandatory emissions disclosure while being acutely aware of the burgeoning issue of illegal refrigerant trade. Through vigilant monitoring of refrigerant use, adoption of appropriate lower GWP alternatives, and strengthening compliance mechanisms, Australian companies can both manage risks and seize opportunities within the emerging low-carbon economy.

Alignment with international best practices does more than ensure regulatory compliance; it elevates Australian businesses to the forefront of the worldwide movement towards responsible cooling solutions. This pivotal moment demands collaboration among government bodies, industries, and innovators to effectively tackle refrigerant smuggling, slash emissions, and spearhead technological advancements.

By adapting proactively to these changes, Australia will not only significantly lower its carbon footprint and address legacy issues but also enhance its standing in the global effort against climate change, promoting both economic fortitude and ecological stewardship.

First published on LinkedIn 17th October 2025